Int J Chem Res, Vol 7, Issue 2, 1-3Research Article

HEAVY CADMIUM METAL DETERMINATION CONCENTRATION IN CHEESE

RUAA R. MUNEAM, ALI ABID ABOJASSIM, GHADEER HAKIM JAAFAR KATHEM

Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, University of Kufa, Iraq

Email: [email protected]

Received: 10 Dec 2022 Revised and Accepted: 20 Mar 2023

ABSTRACT

Objective: The purpose of this study was to look into the concentration of the heavy element Cadmium and its health risks in cheese samples available in Iraqi markets.

Methods: 72 random samples of six country groups (15 Iran, 9 Iraq, 9 Egypt, 15 Turkey, 15 Hungary, and 9 Saudi Arabia) available in Iraqi markets were collected and analyzed using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer, Shimadzu model AA7000, USA.

Results: The highest average Cd metal level in the samples was found in Iranian cheese, while the lowest was in Iraqi ones. The descending Cd order of the countries was Turkey>Hungary>Egypt>Iran>Saudi Arabia>Iraq, according to the T-test confirmation. The daily Cd metal intake ( ), Cd target hazard quotient (

), Cd target hazard quotient ( ), and Cd carcinogenic risk (

), and Cd carcinogenic risk ( ) values were less than the permissible and risk values.

) values were less than the permissible and risk values.

Conclusion: Eventually, the health risk parameters revealed that there are no pose risks from those cheeses to Iraqi consumers.

Keywords: Cadmium heavy metal, Flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer, Carcinogenic risk, Cheese samples

© 2023 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcr.2023v7i2.216. Journal homepage: https://ijcr.info/index.php/journal

INTRODUCTION

Heavy metals are natural elements when compared to the density of water is five times more [1]. When their concentrations increase in the ecosystem, their effect is negative because living organisms need them in limited proportions [2]. Due to the uses of heavy metals such as lead, copper, cadmium, cobalt, silver, etc., especially in recent times in industrial areas, they have contributed to an increase in the exposure of humans and living organisms to them, in addition to their concentrations that are naturally present in the earth’s crust and which contribute to the process of transporting them through air, water, and even rock erosion processes. Untreated industrial and domestic wastes of human activities, such as mining, oil derivatives extraction, factory and hospital wastes, are all sources of heavy metal pollution, causing destruction to the environment and the bodies of living organisms when accumulated in it due to the difficulty of their decomposition [2]. Globally, the problem of heavy metal pollution has become the focus of attention for researchers and international health organizations. Because of its danger and toxicity and the inability of living organisms' bodies to analyze it biologically, metals enter the bodies of living organisms through water, air, soil, and foods contaminated with these metals. Cheese is one of the foods we eat on a daily basis because of the numerous nutrients it contains and the benefits it provides [3]. Heavy metals, one of the most significant and complicated pollutants, can contaminate cheese [4, 5]. Pollution may occurs mainly as per pollutants intake by animal's produced milk or throughout dairy production [6]. Pollution of the environment of livestock and their feed with heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, chromium, nickel, and cobalt leaves its effect by being transmitted in the milk of those cattle at different levels, causing very serious problems [7]. Many surveys around the world used various technical methods to investigate heavy metals in cheese specimens [8–11]. The goal of this survey is to analyze lead concentrations as heavy metals in selected specimens of foreign and Iraqi-made canned cheese using the device of atomic absorption spectrometer technique. Another goal is to reveal carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic health risks to adult consumers of these cheeses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

72 random cheese samples from six countries were collected from different markets in Najaf Governorate, Iraq. 15 samples from Iran, Turkey, and Hungary and 9 samples from Iraq, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia were collected in September 2022. Without delay, the samples were put in polyethylene containers; having identified labels for each sample, they were taken to the laboratory. The identifying label has the name of this sample and all other specific sample information.

Method

According to [12], there was wet digestion for each prepared cheese sample. First, the samples must be dried for 24 h at 70 °C. A solution of HNO3 and HClO4 (10:1) was added to 1 g of each cheese sample, which was then cold digested at room temperature overnight. After 12 h, the mixture was heated and allowed to evaporate, leaving about 1 ml of residue. Each digested sample, after cooling, was filtered in a volumetric flask covered with Whatmann paper after adding 25 ml of DI water to it to be ready for analysis. By using a flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer, Shimadzu model AA7000, USA, all the filtered samples were analyzed.

Calculations

Daily Cd metal intake ( )

)

Depending on the Cd concentrations  in

in  units in the cheese samples, the estimation of daily Cd intake (

units in the cheese samples, the estimation of daily Cd intake ( ) from the cheese consumption done by the formula [8, 13]:

) from the cheese consumption done by the formula [8, 13]:

For adults, the average body weight (BW) in  was taken 70, in this study, and the weight of the consumption cheese

was taken 70, in this study, and the weight of the consumption cheese  daily in

daily in  was 0.022 [8, 14].

was 0.022 [8, 14].

The Cd target hazard quotient ( )

)

By depending on the daily Cd metal intake in equation (1) and the dose of the daily oral reference ( ) in

) in  for Cd which equals to

for Cd which equals to  [15, 16], the Cd target hazard quotient can be found from the formula [17, 18]:

[15, 16], the Cd target hazard quotient can be found from the formula [17, 18]:

The Cd carcinogenic risk ( )

)

The  value due to the populations Cd exposure calculated by the formula [19]:

value due to the populations Cd exposure calculated by the formula [19]:

Exposure frequency to the Cd (EFr) in days per year was 350, while 30 y is the duration of exposure to the Cd (ED), and 365 was the average daily time per year (AT) [20]. The daily ppm of the oral carcinogenic slope factor from the Cd ( ) was 15 [21].

) was 15 [21].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

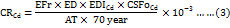

By using the atomic absorption spectrophotometer technique, Cd concentrations and the related health risk parameters were estimated in 72 canned cheese samples which available in Iraqi markets. Table 1 includes the findings of Cadmium concentrations of cheese samples as averages, as well as, the average health risk parameters. It revealed that the rates of Cd concentrations in ppm units for the selected samples of cheese of this study were higher in Turkish cheese while lower in Iraqi ones. The maximum value of average Cd concentration in Turkish samples is attributable to the variation between Iraqi and foreign samples, as well as sample storage manners in Iraqi markets. The average Cd concentration levels in cheese samples were above the maximum rate of the EC Commission, Codex standards, and EU Regulations 0.05 ppm [21, 22], as shown in table 1. But the accumulation results because of the long-time consumption revealed that all risk parameters of health as the Cd heavy metal in the investigated cheese samples of this study below the recommended level. The  and

and  of all of the tested cheeses used in this survey found to be below the global limits 1.0

of all of the tested cheeses used in this survey found to be below the global limits 1.0  and 1, respectively [23, 24]. The carcinogenic risk outcomes

and 1, respectively [23, 24]. The carcinogenic risk outcomes  as per Cadmium concentrations is depicts in table 1.

as per Cadmium concentrations is depicts in table 1.  Values for tested cheeses diverse from one country sample to another. Referring to the recommended ranges of the Environmental Protection Agency

Values for tested cheeses diverse from one country sample to another. Referring to the recommended ranges of the Environmental Protection Agency  [20], the

[20], the  average results for tested cheeses have limits under the recommended. Fig. 1 shows a comparison between the rates Cd concentrations in the current study in selected canned cheese samples and other country studies (India [10], Georgia [11], Bulgaria [25], and Bangladeshi [23]) which referred that the current study times higher. The descending order of the countries of the average results of cheese was Turkey>Hungary>Egypt>Iran>Saudi Arabia>Iraq, as per to the T-test confirmation. The variations in the Cd concentration ranges of all specimens are significant (p<0.05) for a range of factors, which would include pollution by Cadmium in plants consumed by milk-producing animals, pollution during the cheese manufacturing operation, and pollution by the different types of cheese packaging canned, among others.

average results for tested cheeses have limits under the recommended. Fig. 1 shows a comparison between the rates Cd concentrations in the current study in selected canned cheese samples and other country studies (India [10], Georgia [11], Bulgaria [25], and Bangladeshi [23]) which referred that the current study times higher. The descending order of the countries of the average results of cheese was Turkey>Hungary>Egypt>Iran>Saudi Arabia>Iraq, as per to the T-test confirmation. The variations in the Cd concentration ranges of all specimens are significant (p<0.05) for a range of factors, which would include pollution by Cadmium in plants consumed by milk-producing animals, pollution during the cheese manufacturing operation, and pollution by the different types of cheese packaging canned, among others.

Table 1: Averages and standard errors of Cd calculations

| Country |  ppm ppm |

|

|

|

| Iran | 0.135±0.029 | 0.050±0.010 | 0.050±0.010 | 0.305±0.067 |

| Iraq | 0.131±0.025 | 0.048±0.009 | 0.048±0.009 | 0.297±0.057 |

| Egypt | 0.139±0.040 | 0.050±0.014 | 0.050±0.014 | 0.314±0.091 |

| Turkey | 0.167±0.032 | 0.061±0.012 | 0.061±0.012 | 0.378±0.074 |

| Hungary | 0.141±0.026 | 0.051±0.009 | 0.051±0.009 | 0.320±0.059 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.134±0.036 | 0.049±0.013 | 0.049±0.013 | 0.303±0.083 |

| Allowed Values | 0.05 [21, 22] | 1 [23] | 1 [24] | 10-4-10-6 [20] |

Fig. 1: Comparison between current and other country studies

CONCLUSION

The results of the present study, related to the Cd concentrations, indicated that the analyzing results of the samples, according to the EC commission, codex general standard, and European regulations, compared with the world averages, were found to be the highest. However, the findings of the non-carcinogenic (

and

and

) and carcinogenic health risk parameter

) and carcinogenic health risk parameter

based on the Cd concentrations were permissible within the global limits. Eventually, the risk parameters of health revealed that there are no pose risks from those cheeses to Iraqi consumers.

based on the Cd concentrations were permissible within the global limits. Eventually, the risk parameters of health revealed that there are no pose risks from those cheeses to Iraqi consumers.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. R. R. Muneam carried out the experiment and wrote the manuscript. A. A. Abojassim and Ghadeer Hakim Jaafar Kathem does the calculations and the electronic correspondence. All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

-

Abojassim AA, Munim RR. Hazards of heavy metal on human health. In: Research trends in multidisciplinary research, AkiNik Publications New Delhi; 2020. p. 51-67.

-

Jarup L. Hazards of heavy metal contamination. Br Med Bull. 2003;68(1):167-82. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg032, PMID 14757716.

-

Fox PF, Guinee TP, Cogan TM, Mcsweeney PLH. Fundamentals of cheese science, 2 nd. New York: Springer US; 2016.

-

Muneam RR, Abojassim AA. Assessment of carcinogenic and noncarcinogenic health risks for selected heavy metals of Egyptian and Saudi Arabia cheeses in Iraqi markets. Ann Biol. 2022;38(1):123-7.

-

Louya OT, Anselme AL, Abarin GG. Toxicological analysis of heads and headless parts of jawfish, tuna, tilapia and mackerels consumed in the Abidjan City (Côte d’Ivoire). Int J Curr Res. 2022;14(11):22710-3.

-

Pavlovic I, Sikiric M, Havranek JL, Plavljanic N, Brajenovic N. Lead and cadmium levels in raw cow’s milk from an industrialised croatian region determined by electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry. Czech J Anim Sci. 2004;49(4):164-8. doi: 10.17221/4295-CJAS.

-

Abou Arab AAK. Effect of ras cheese manufacturing on the stability of DDT and its metabolites. Food Chem. 1997;59(1):115-9. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(96)00214-2.

-

Christophoridis Ch, Kosma A, Evgenakis E, Bourliva A, Fytianos K. Determination of heavy metals and health risk assessment of cheese products consumed in Greece. J Food Compos Anal. 2019;82:1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2019.103238.

-

Reinholds I, Rusko J, Pugajeva I, Berzina Z, Jansons M, Kirilina Gutmane O. The occurrence and dietary exposure assessment of mycotoxins, biogenic amines, and heavy metals in mold-ripened blue cheeses. Foods. 2020;9(1). doi: 10.3390/foods9010093, PMID 31963130.

-

Singh M, Ranvir S, Sharma R, Gandhi K, Mann B. Assessment of contamination of milk and milk products with heavy metals. Indian J Dairy Sci. 2020;72(6):608-15. doi: 10.33785/IJDS.2019.v72i06.005.

-

Al Sidawi R, Ghambashidze G, Urushadze T, Ploeger A. Heavy metal levels in milk and cheese produced in the Kvemo Kartli region, Georgia. Foods. 2021;10(9):1-20. doi: 10.3390/foods10092234, PMID 34574344.

-

Rashid MH, Fardous Z, Chowdhury MAZ, Alam MK, Bari ML, Moniruzzaman M. Determination of heavy metals in the soils of tea plantations and in fresh and processed tea leaves: an evaluation of six digestion methods. Chem Cent J. 2016;10(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s13065-016-0154-3, PMID 26900397.

-

Meshref AMS, Moselhy WA, Hassan NEY. Heavy metals and trace elements levels in milk and milk products. Food Measure. 2014;8(4):381-8. doi: 10.1007/s11694-014-9203-6.

-

Renner E. Nutritional aspects of cheese. In: Cheese: chemistry, physics and microbiology. Springer Publishing; 1993. p. 557-79.

-

USEPA. Baseline human health risk assessment for the standard mine site Gunnison County, Colorado. Syracuse Research Corporation. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 8; 2008.

-

Zhuang P, Mcbride MB, Xia H, Li N, Li Z. Health risk from heavy metals via consumption of food crops in the vicinity of dabaoshan mine, South China. Sci Total Environ. 2009;407(5):1551-61. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.10.061, PMID 19068266.

-

United States. Environ Prot Agency. “Office of water regulations and standard: guidance manual for assessing human health risks from chemically contaminated fish and shellfish.” [Washington, D. C.]: U. S.; 1989.

-

Khalil OSF. Risk assessment of certain heavy metals and trace elements in milk and milk products consumed in Aswan Province. J Food Dairy Sci. 2018;9(8):289-96. doi: 10.21608/jfds.2018.36018.

-

Usepa III. Risk-based concentration table: technical background information; 2006.

-

USEPA. Risk-based concentration table; 2010.

-

EC commission regulation. Commission regulation (EC) no 1881/2006 of 19 Dec 2006 setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs (Text with EEA relevance). Off J Eur Union. 2006;364(1):5-25.

-

Codex S. Codex general standard for contaminants and toxins in food and feed; 1995.

-

Tripathi RM, Raghunath R, Sastry VN, Krishnamoorthy TM. Daily intake of heavy metals by infants through milk and milk products. Sci Total Environ. 1999;227(2-3):229-35. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(99)00018-2, PMID 10231985.

-

Islam MS, Ahmed MK, Habibullah-Al-Mamun MH, Masunaga S. Trace metals in soil and vegetables and associated health risk assessment. Environ Monit Assess. 2014;186(12):8727-39. doi: 10.1007/s10661-014-4040-y, PMID 25204898.

-

Karadjova I, Girousi S, Iliadou E, Stratis I. Determination of Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, Ni and Pb in milk, cheese and chocolate. Mikrochim Acta. 2000;134(3-4):185-91.